MLB A's, A's Baseball, Alex Colome, Analytics, Baseball, Baseball Hall of Fame, Brewers, Brewers Baseball, Bruce Sutter, Chicago, Chicago Baseball, Chicago Cubs, Chicago Sports, Chicago White Sox, Closer, Cubs, Cubs Baseball, Dan Quisenberry, Doug Corbett, Edwin Diaz, ERA, fERA, Fireman, Fireman ERA, Goose Gossage, HOF, Kansas City Royals, Kirby Yates', Liam Hendriks, Mariano Rivera, Mets, Mets Baseball, Milwaukee Brewers, MLB, MLB News, Neil Allen, New York, New York Mets, New York Yankees, Oakland, Oakland Athletics, Padres, Padres Baseball, Pitchers, Relief Pitchers, Rollie Fingers, Royals, Royals Baseball, Sabermetrics, San Diego Padres, Save, Sports, Statistics, Stats, Tom Burgmeier, White Sox, White Sox Baseball, Yankees, Yankees Baseball Jon Zaghloul 0 Comments

fERA 2.0: Comparing 1980 to 2019

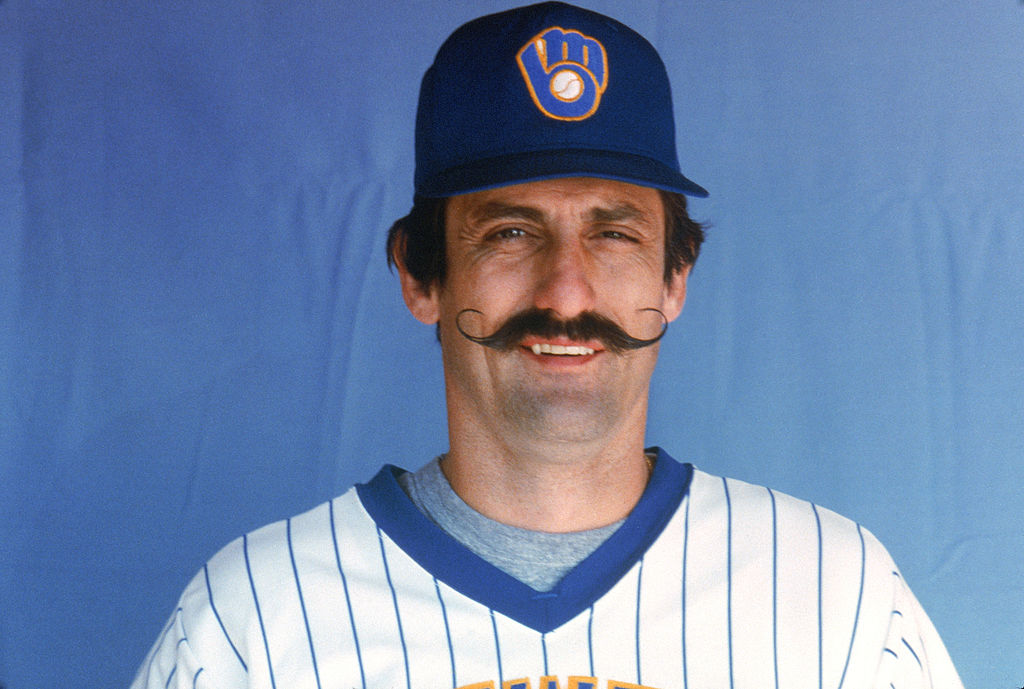

Rollie Fingers. Goose Gossage. Bruce Sutter.

All three of these Hall of Fame closers are generally considered to be the pioneers of their position. They each recorded 300 saves, began their rise in the mid-1970s, and today, symbolize the gold standard of saving games.

They also accomplished feats, though, that are simply baffling when compared to the context of the modern-day closer. For instance, Gossage and Sutter had more saves of at least two innings than saves where they pitched one inning or less (“Closer (Baseball)”). Similarly, Fingers is the only pitcher in baseball history to pitch at least three innings in more than 10 percent of his saves (“Closer (Baseball)”).

Nevertheless, it’s no secret that these statistical anomalies are otherwise obsolete today. The closer position has undergone a drastic shift over time, moving away from the traditional “fireman” role, to now, a single-inning flamethrower intent on shutting down games. That said, is there a way to compare both eras and determine which one produced the better closer?

Fortunately, “Fireman ERA,” or fERA for short, can provide some much-needed insight. fERA, as previously documented, is a subset of a closer’s regular ERA, yet specifically measures a closer’s performance when he pitches in innings other than the final inning of a game. It does not include innings in which the closer costs his team a lead, then forces them to play extra innings, as, in that case, the closer originally enters the game under the impression of pitching his final inning.

As of this article, however, fERA does include innings that are tied when the closer enters the game. This change was made because the closer, when coming in, is not operating under the assumption of a save situation. Instead, he enters under the notion that the current inning will not be the game’s final inning, thereby qualifying in terms of fERA standards.

To better visualize this circumstance, think of walk-off hits that occur during tie games. At the beginning of the inning, the closer enters with an even score. He is not anticipating this to be the game’s final inning. Once he gives up the walk-off hit, though, the inning subsequently becomes the last one. In the same sense, imagine the closer is on the home team. If he shuts down the opposition, then his team produces a walk-off hit in the bottom half of the frame, that too does not represent the final inning, per se. The closer came in with a tie score; he did not know it would be the game’s final inning until after the fact. Therefore, in that instance, it again will count as an fERA inning.

To test and implement this statistic, data from both 1980 and 2019 was used. In determining which closers to include in the study, those who achieved 20 or more saves were considered. That total, albeit arbitrary to some, was attained by 22 players in 2019 and 14 players in 1980, and separates season-long closers from intermittent closers.

2019 Data Set: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/13sMadDXHJ6Vn6bxFUlWwtRc8oWo3NP9t1HSjOhUGTdo/edit?usp=sharing

1980 Data Set: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1FkVml1fbZ_aUFwbey8w5ZQni7i17lcUK-sUccJebpLs/edit?usp=sharing

In each of the data sets, the closers’ total innings pitched, earned runs, and ERA were calculated first. Then, via Baseball Reference’s individual game logs, each closers’ total innings figures were separated into two categories: innings pitched (last inning only) and innings pitched (besides last inning). The earned runs charged to the closers in those specific innings were also separated accordingly. The resulting ERA from dividing the earned runs by the innings pitched (besides last inning) creates fERA.

Out of the 22 closers in question from 2019, Will Smith was the only one to record a 0.00 fERA. Additionally, Liam Hendriks, who led all closers with 47 innings pitched besides the final inning, posted an impressive 1.53 fERA. Kirby Yates, who had the top overall ERA in the data set at 1.19, finished with a surprisingly-high 4.09 fERA. And, Alex Colome, of the Chicago White Sox, not only produced the worst fERA with a 6.55 mark, but also garnered the largest difference, in the wrong direction, between regular ERA and fERA. In other words, his fERA was 3.75 points higher than his overall ERA in 2019.

In contrast, not one closer from 1980 posted a 0.00 fERA; the lowest mark belonged to Tom Burgmeier at 1.88. Doug Corbett, who led all closers with 84.1 innings pitched besides the final inning, posted an even more impressive 2.03 fERA. Dan Quisenberry, who paced the data set in total innings pitched, recorded the smallest difference between fERA (3.11) and overall ERA (3.12). And, Neil Allen, in a similar fashion to Alex Colome, produced the worst fERA at 5.38, but also sported the largest difference, in the wrong direction, between regular ERA and fERA. That said, his fERA was only 1.67 points higher than his overall ERA in 1980.

On a broad scale, two fascinating trends also arose that deserve increased scrutiny. For starters, in 2019, 11 of the 22 closers recorded an fERA lower than their regular ERA. Likewise, in 1980, 6 of the 14 closers saw their fERAs lower than their overall ERAs. This can suggest that those within this category are more effective in multiple inning appearances, yet it is important to note that these specific innings do not match the intensity that accompanies a final inning save situation. Thus, although these closers are turning in productive performances in innings besides the last one, the circumstances they inherit are far less tense.

The second and just as intriguing trend involves the closers’ ERAs in the last inning of a game. In the 2019 data, 11 of the 22 closers posted higher ERAs in the final inning compared to their overall ERA. In 1980, however, only 6 of the 14 closers possessed this same characteristic. Theoretically speaking, the final inning of a game provides suspense and intensity that cannot be matched by any of the preceding innings. In this case, though, half of the closers from 2019 and the majority of closers from 1980 found it easier to pitch in a game’s last inning, compared to the ones prior. The most likely explanation for this phenomenon involves an influx of low-leverage last innings pitched. For example, if a closer enters the game’s final inning with a five-run lead, and subsequently shuts the door, that inning does not count toward fERA; it is still considered apart of his “last inning” ERA. Within that instance, the usual last inning suspense is non-existent, ergo making the closer’s objective less difficult to attain.

Now, when directly comparing 1980 to 2019, instead of grouping both years together, it immediately becomes apparent that the closers of the past are much better than their modern-day equivalents. In the final row of each data set, the averages of the closers from both seasons have been calculated. Closers from 1980 averaged more innings pitched, lower overall ERAs, lower fERAs, and lower final inning ERAs compared to closers from 2019.

Although a “higher sample size” argument will be made by detractors to discredit the 1980 closers’ achievements, it is, without question, a flawed case. It has already been established that the closers from 1980 pitched more innings, on average, than those in 2019. That said, their average ERA is still 0.21 points lower than their 2019 counterparts. With a higher volume of innings, the opportunity to give up more runs, and thus, heighten the average ERA, is an ever-present danger. That’s why, in theory, it should follow that 2019 closers have a lower average ERA than those from 1980. Obviously, that is not the case. And even if, hypothetically, 2019 closers pitched the same amount of innings, on average, as the 1980 closers, their average ERA would maintain the same value, thereby furthering the point that yesteryear’s closers are superior to their equivalents today.

Goose Gossage, in response to a claim that Mariano Rivera is the greatest relief of all-time, said, “Don’t tell me [Rivera’s] the best relief pitcher of all-time until he can do the same job I did” (“Closer (Baseball)”). Gossage’s comment, although unpopular, is supported by the data presented in this study. He, along with his contemporaries of 1980, clearly surpass the closers of today. They may not have recorded as many saves, but they pitched in more innings, posted lower ERAs and fERAs, and, in turn, gave their position a true definition. That, by far, rivals and exceeds what today’s closers have to offer.

References

“Closer (Baseball).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation Inc., 18 Dec. 2020,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closer_(baseball).

Share this content: